[ad_1]

With most of the developed world on lockdown, and markets and economies paralyzed until there is a material decline in new coronavirus cases, i.e., until we slide “over the hump” of the coronavirus curve, the biggest question – and variable – in assessing the economic damage unleashed by the covid-19 virus is the length of the lockdowns now in force, with Deutsche Bank’s Luke Templeman pointing out that “politicians and health officials have discussed dates ranging anywhere from weeks to over a year.”

In an attempt to answer this most important for capital markets question, namely when will the civic and economic restrictions begin to be lifted in various key countries, Deutsche Bank provides some estimates largely based on the experience of the lockdown and reopening in China’s Hubei province.

Using the “Chinese” experience as indicative of what other countries can achieve, recent studies have confirmed that after implementing various suppression measures, several large countries “appear to be converging onto the decline in the daily growth rate of deaths” seen in China. An Imperial College study in particular pointed out that the overall number of deaths in other countries could be between two and eight times the number of deaths as in China.

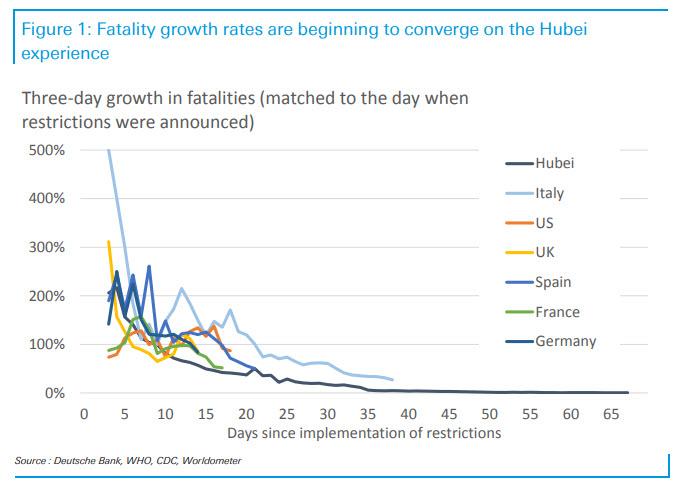

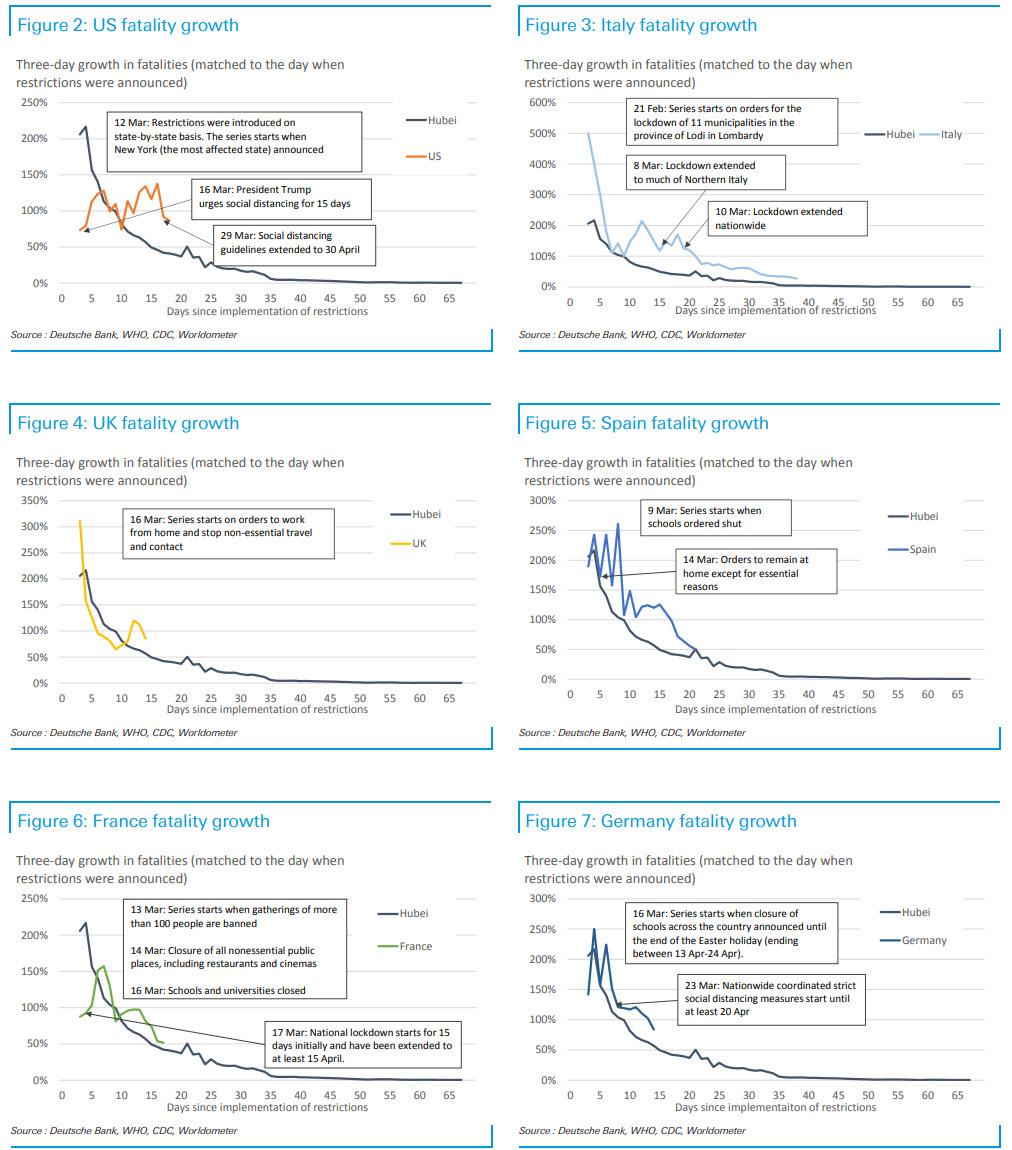

As DB notes, one way to look at how other countries are converging on the experience in Hubei province, China is shown in the following chart. As the German bank explains, it uses “a three-day comparison in order to filter out the noise from sudden jumps and drops when figures were relatively small. We also start each time series at the point at which restrictions were introduced to attempt a closer comparison. We then show all the countries individually against the Hubei experience.”

With that in mind, here’s China:

… and the rest of the countries that have reported the most fatalities to date:

Looking at the charts above, at first glance it appears that the growth rate in the number of fatalities in Hubei province is falling faster than that in other countries. This is true, however, according to DB it does not invalidate the comparison of Hubei with other countries. That is because Hubei implemented restrictions earlier in the process of infection than did some other countries with the US being the laggard. There is also that fact that, whether anyone wants to admit it or not, China’s data has been chronically fabricated and the Wuhan baseline is at best a stylized interpolation of what Beijing wants the world to see even as it continues “one of the worst coverups in human history.”

That said, one must also add to this is the fact that the six other countries examined here have a greater proportion of people in the population that classify as high risk (primarily the elderly). As such, it is not unexpected that the fatality growth curves of these six countries initially lagged that of Hubei.

Despite all these complicating circumstances, a comparison with the Hubei experience is still worth examination. While it is early days, most of the charts indicate each country’s fatality trajectory are now converging (in different stages) with that of Hubei.

There are certainly outliers. For instance, Germany still has a relatively low number of deaths which has made the calculations swing considerably. Meanwhile, the US still shows a fatality growth rate that is not on an obviously downwards trajectory. Still, it must be noted that there can be a 14-day lag between restrictions and outcomes, and President Trump only urged social distancing on 16 March (while our time series starts at 12 March when New York implemented restrictions). Coupled with this, different states in the US have implemented restrictions at different times. Despite this, the Imperial study mentioned earlier specifically indicated that the US began to show convergence with China last week now that many states have implemented lockdowns.

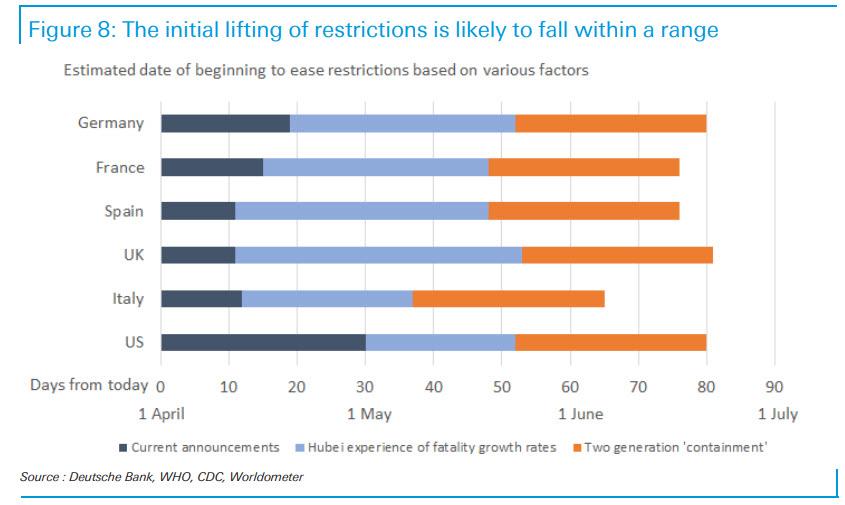

In summary, extrapolating the Hubei experience of lockdown and the beginning of lifting restrictions gives us an indication of when other economies can be reopened even if the timing is unlikely to exactly match.

When will restrictions be lifted?

So with a whole host of caveats, the following chart from DB shows a ‘football field’ representation of the range of possible timelines for the restart of activity in several countries. It includes the current period of lockdowns and the projected time line based on extrapolating the Chinese response. It is likely these countries will begin to loosen restrictions within the range based on the Hubei experience (light blue bar).

To be sure, the decision to relax restrictions depends very heavily on how the epidemic curve in each country progresses. This progression reflects decisions made up to 14 days earlier given the likely incubation period of the virus. In Hubei, the three-day growth rate in new cases decreased from over 200 per cent to 63 per cent in the 14 days after restrictions were put in place. Ultimately, it was 63 days after the restrictions were put in place until they were lifted.

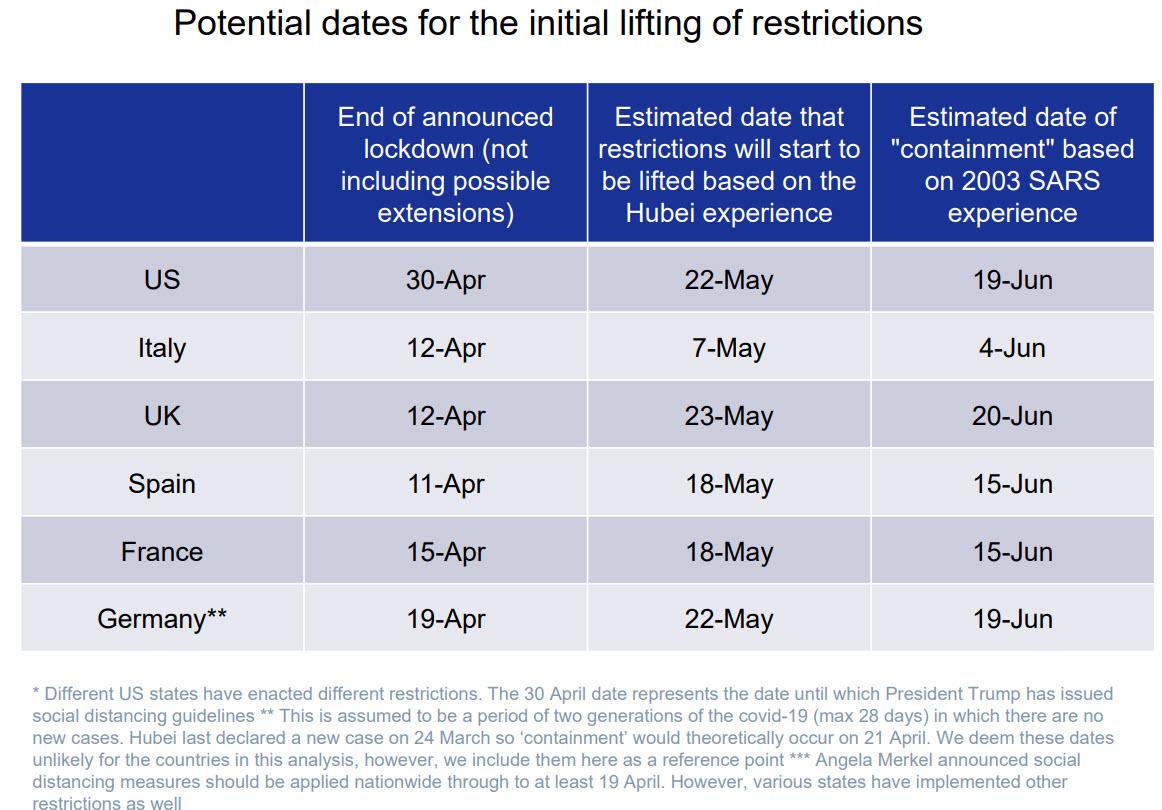

The following table summarizes the potential dates that restrictions on civic and economic activity could end in various key countries.

Here one more caveat: as a reminder, the focus of impact in China was different from that of other countries. China managed to implement restrictions on Hubei that kept the majority of the impact inside the province by effectively streamrolling over the civic liberties of millions of people, something most democratic countries are unable to do with the stroke of a pen the same way Beijing did. Additionally, many other countries have seen the virus enter their borders via different channels – some of which have yet to be confirmed – which can and will change the timeline for the breadth of the spread. Finally, political pressure from different groups in western countries may result in pressure to reopen earlier than the Hubei timeline.

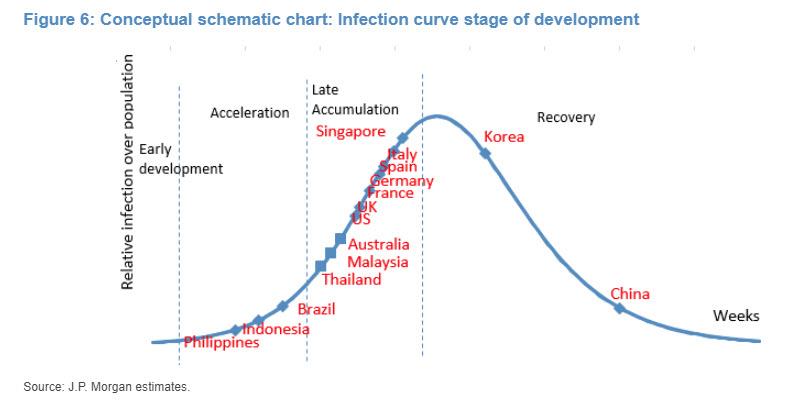

That said, as JPMorgan observed on Friday, with every passing day the list of countries in the “late accumulation” phase are getting closer to the curve apex after, at least in theory, follows a recovery.

That said, if governments rush to reopen economies, if new clusters re-emerge, or if the virus mutates rendering any existing antibodies within the population irrelevant, the whole process begins from square one.

Unfortunately for Europe which was already on the verge of recession well before the Coronavirus breakout, waiting patiently is a luxury the continent can not afford, and as the FT reports today, “governments across Europe have begun preparations to ease the lockdowns imposed across much of the continent to contain the coronavirus pandemic, even if restrictions that have paralyzed the economy are expected to remain in force for several more weeks.”

In short, Europe is preparing to become China, which after an initial period of aggressive quarantines, forced the entire nation back into the office even though new cases continue to flare up and a second cluster now appears to have emerged.

France, Spain, Belgium and Finland are among many countries that have set up expert committees to examine a gradual easing of stay-at-home orders for some businesses and schools while avoiding a second wave of infections that could overwhelm health services.

Pedro Sánchez, the Spanish prime minister, on Saturday extended the shutdown of his country for another two weeks until April 26 but he said a ban imposed last month on all non-essential work including manufacturing and construction would be lifted after Easter.

“When we have the [infection] curve under control, we will shift towards a new normality and towards the reconstruction of our economy,” Mr Sánchez added. “A specific team of epidemiologists has been working for two weeks now on a plan to restart economic and social activity.”

Angelo Borrelli, head of Italy’s Civil Protection Agency which is in charge of co-ordinating the national response to the outbreak, suggested a “phase two” of the country’s lockdown could begin next month: “I don’t want to give dates, but between now and May 16 we may have further positive data that suggests we can resume activities and then start phase two,” he said.

Édouard Philippe, the French premier, said last week that the process of “deconfinement” had no precedent and would be “fearsomely complex”, adding: “We are probably not heading for a deconfinement that would be absolute everywhere for everyone.”

Denmark, which was one of the first countries in Europe to shut down activity and close its borders, last week became the first to put a timetable on the loosening of restrictions: “If we Danes for the next two weeks — beyond Easter — continue to stand together, at a distance, and if the numbers remain stable and reasonable, then the government will begin a gradual, quiet and controlled opening of our society again,” Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said on March 30.

Germany, where the daily rate of confirmed coronavirus cases and deaths has risen in recent days, has also begun preparing what one official called a “phase-out” that would be “acceptable in terms of health policy”. “But we’ve been careful about what we say in public,” he added.

“The important message now is: we are not in a phase of the pandemic where we can tell people the measures can now be relaxed,” Steffen Seibert, spokesman for German chancellor Angela Merkel, said on Friday. “Of course you can prepare for that mentally, but for the moment it’s this [stay-at-home] message that matters.”

Few other governments are willing to put a timescale on the loosening of restrictions not least because, according to most experts, it will require a massive increase in testing capacity. Many also worry about undermining the stay-at-home message with the onset of the Easter holidays and warmer weather and with populations already chafing at weeks of confinement and the loss of earnings.

Meanwhile, experts warn it is a big mistake for governments not to engage the public in a debate about loosening restrictions: “Although it is clear we cannot talk about when the opening up will take place, we can talk about how,” said Christiane Woopen, professor at the University of Cologne’s Center for Ethics, Rights, Economics, and Social Sciences of Health and a scientific adviser to the government of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany’s most populous region.

“The public deserve it. They are taking a lot of hardship. They have to trust what political leaders are doing in the next months.

And then there is the worst case scenario: prof Woopen is one of a dozen academics — epidemiologists, physicians, lawyers and economists — who published a report last Friday for the Munich-based Ifo economics institute. The report is an attempt to frame what Prof Woopen calls an “opening strategy, not an exit strategy”, since there is unlikely to be any return to normality before a reliable vaccine against Covid-19 becomes widely available, which appears to be at least a year away.

Finally, even if Deutsche Bank is right and the lockdowns are lifted some time in late May/early June, any loosening of restrictions would have to be accompanied by a ramping up of testing, said Martin Lohse, professor of pharmacology at the University of Würzburg, and another of the Ifo report’s authors.

Even Germany’s extensive testing – it was conducting 50,000 a day last week – is insufficient given its population of 80m, he said. Antibody testing would also be indispensable even if none of the tests being trialled around the world was so far deemed accurate enough. And governments needed to boost production of protective equipment as the wearing of face masks becomes more widespread. France for example is now considering making face masks mandatory in public.

More rigorous contact tracing and tracking via mobile phone apps, would also be essential, Prof Lohse added.

In short, a reopening of the economy would likely entail the introduction of a smartphone based “bio-passport”, where any person who wishes to “reenter society” will have to not only undergo some form of daily testing to confirm they are virus free, but also effectively hand over most if not all privacy to the government. Needless to say, the long-term sociological consequences of such a collectivization of private information will be unlike anything seen in recent history.

[ad_2]

Source link